Mental Health: It’s Personal

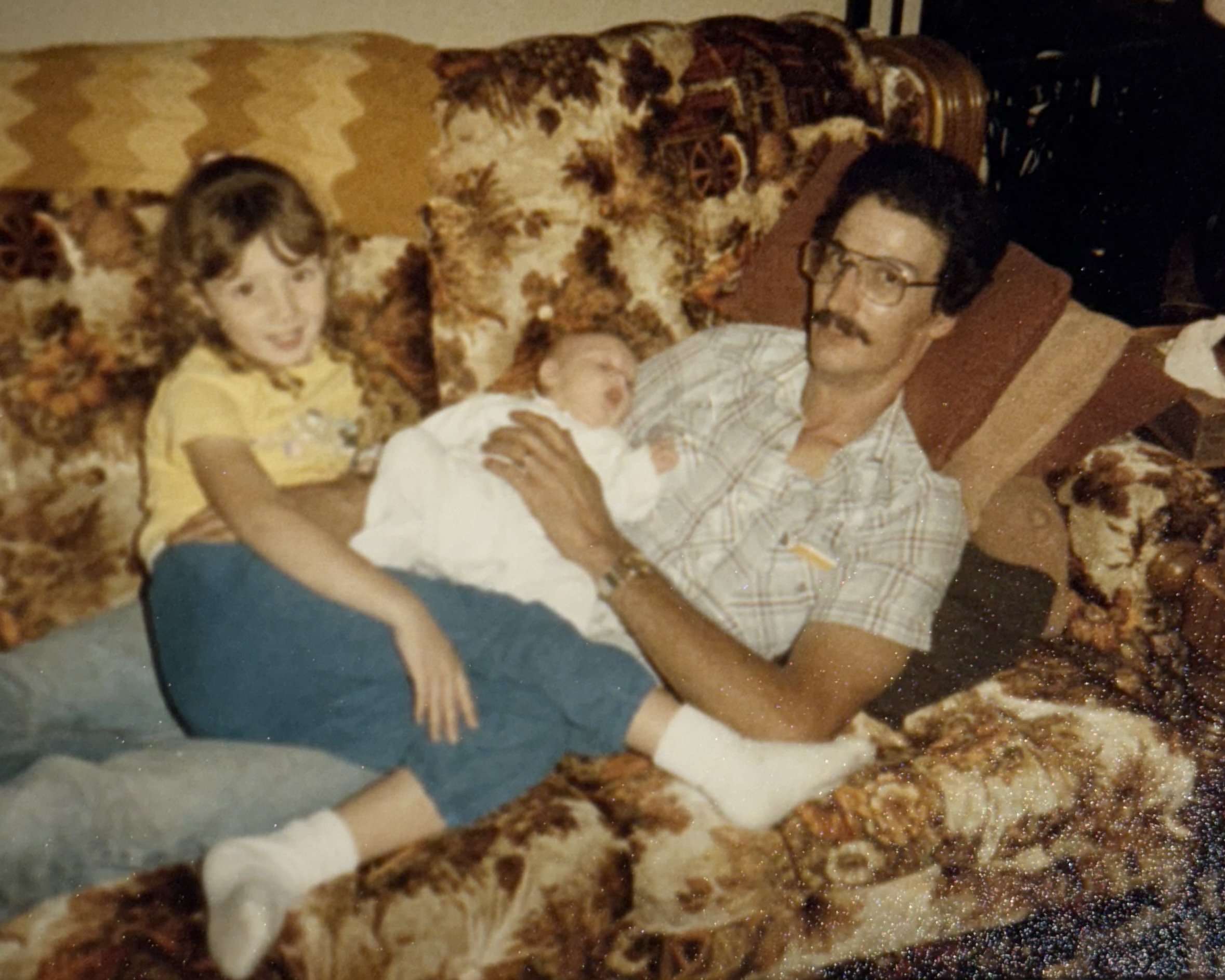

My father and I on a textbook 80’s sofa.

Growing up, I never considered my story to be special or unique. Much of what happens to us in life isn’t by way of choice, we just manage the situations the universe puts us in. I am no different, however when I do share my story I am often told otherwise. I still don’t feel it, but if I am told my story can help just one person, then it is worth sharing.

I grew up in a small town in Ohio where everyone knew each other. My home life was typical; one mom, one dad, one sister 5 years younger than me. My father was a truck driver and a diesel mechanic, often working 2nd shift. He had a large garage in the back yard where he had a constant stream of side work for friends repairing cars, trucks, and semis. This is where I grew up, often on a creeper right alongside him under a car handing him tools as we talked.

Before my sister was born and before I started school, I was often cared for by my dad while my mom worked. It also meant I spent a lot of time in the local bars. I just thought it was fun to play pinball while the bartender made sure I had an endless platter of “the cheese with the holes” (Swiss cheese), pickles, and a glass of root beer. I was raised by my father and many of the friends who frequented his shop and the bar, an incredible group of blue-collar men with backstories they drowned in their drinks. At that age, I didn’t know that wasn’t “normal”.

My Dad’s own backstory wasn’t uncommon; divorced parents, an abusive stepfather. He escaped his childhood and fell in love with my mother. Not long after their wedding my own mom’s mother was murdered, and my parents took custody of my twin 13-year-old aunts. Not long after that I came into their world, and he fell in love again. I was born into a family recovering from a tragic loss and learning to live under one roof, but it was awesome having two older “sisters”.

Then at his 30th birthday party he hopped on a friend’s motorcycle for a quick ride and didn’t come back. A car had run him off the road and he would spend the next month recovering in the hospital. This was just another one of the many curveballs the universe threw at my family, but it was what I knew life to be. Life with my father after his accident was different, but it meant more time together while he was on disability. More “cheese with the holes” and root beer while mastering pinball. He eventually recovered, but not without lasting physical and mental pain. He drank more to cope.

Then at some point it was too much. My Dad, who stood 6’6” tall, had days that crushed him and literally brought him to the floor. I remember how he seemed so small, and I glimpsed the boy he once was, hurting. He made attempts to take his life. We would often walk in on him, even my sister who was just a toddler. I talked about this with my friends who didn’t understand, but when you’re a kid you don’t recognize your family is different. The school put me into a support group with the guidance counselor; kids with parents who drank too much. No one had stories like mine. This was just our family, we worked together to keep Dad with us, and we loved each other. It was what we did.

When I was 11, I spent a week home from school sick left in the care of my dad. That week would be our last together. We talked, a lot. He shared a lot of details with me about his declining mental health. He cried, I held him. It was just what we did as a family, we cared for and loved each other. It didn’t matter that I was just a child, he needed someone to love him and that is what I did. With all my heart. At the end of that week my sister and I would head to sleep over at our friend’s houses, and when we came home our father wouldn’t be there. He ended his life on March 2, 1996 at 38 years old.

The years that followed were without a doubt the most difficult in my life. In August 1996 I started middle school, then entered my teenage years. My Mom had to work more to pay the bills and had to cope with her own emotions. My little sister was often my responsibility, and she was just the pain in the butt any little sister would be, but she was mine and I loved the time with her. Added to this was that my sister didn’t know how my father had died, so I didn’t have her to talk to. She was only 6 when he died, and I understand the decision not to tell her, but it meant I was even more isolated.

I had a lot of emotions to process during this time as any teenager does, but I didn’t know then how unique my circumstances were. At school I was “that girl who lost her father to suicide” – a shameful label, so talking to friends wasn’t an option. At home I was so angry with my mother, how had we lost the battle and lost dad? The typical mother/daughter fights had an extra layer of guilt and loathing. I’m not proud of the things I said during those years. My Mom has been through so much and still remains the most caring soul you’ll ever meet. She also tried her best to get me to therapists to talk, but I never trusted them enough to allow them to help.

When I was 16 years old a friend took her own life. Her family and I bonded over our shared experiences losing a loved one. We sat together and asked the question we all ask when we lose a loved one to suicide; why? She had recently come out to her family and was openly in a same sex relationship at school, and they supported her. We, like so many survivors, never knew the answer. She was the first of many friends lost to suicide, and it felt like the first time I had someone I could trust to talk to about my own loss.

When we lost my father, we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t openly share how he died. For most of my adult life when I shared that I had lost my father, my response to “how did he die” was often “an accident” or “his declining health” – not exactly lies, but not the truth. At first, I could only talk about it when I was drinking, then I became more accustomed to sharing openly. I met other survivors who had lost loved ones to suicide, and through many years of gracious humans listening to my story and sharing their own, I began to heal.

I am now married, with two kids. My oldest son has the same tall, thin, muscular build my father had and many of his same mannerisms. My youngest son has the same one-sided chin dimple. They know I lost my dad, but they don’t know how. I am not ready for that conversation. Part of me believes if they don’t know suicide is an option then they won’t ever try it themselves. The other part doesn’t want to risk burdening them with the same emotional baggage I’ve carried for years. My oldest is currently 11, the same age I was, and I can’t imagine him experiencing the things that I did at that age.

If you have lost a family member to suicide, then you likely know what it is like to wonder if it is hereditary and constantly scan the depths of your soul looking for signs you inherited the same demons. You may have spent time trying to understand what they felt, what they saw. What made them feel like there was only one way out? Perhaps you have also spent time burying your negative emotions, are afraid of the uncomfortable, and keep running away from the dark places that exist in your mind. If you can’t see them, they won’t find you. You won’t allow them to overcome you, you won’t fall into the same trap.

I’ve been there. I’ve buried a lot, told as a child that strength is not crying. Most of us who were raised in what is now known as the 1900s were raised the same way; and we don’t blame our parents, we blame society. We didn’t have researchers like Brené Brown to study shame and vulnerability, openly sharing the message that vulnerability is strength. The term “shadow work” wasn’t trending, which is the practice of exploring the emotions we have repressed. Like secrets, the emotions we repress always surface. Most often for me it is at night, when the house is dark, and everyone is asleep. I have come to accept that the wounds left by my loss will never heal, and without warning something rips them open, reminding me that the work to heal will never be done.

If you have lost a family member to suicide and now have children, you have likely looked at them and wondered, did it skip a generation? Every negative emotion they feel triggers an emotional response in us that others don’t experience. We are biologically wired to respond to their cries, but for us there is an added layer with that constant search for those emotional demons. In my brain is a small voice that likes to remind me that I was not able to save my dad; will I be able to save them if the time comes? Will the time come? What follows is an investment in their mental health in a way that becomes borderline obsessive. Perhaps it is obsessive, truth be told I’m too invested to be a fair and impartial judge. When my kids are having a hard day, we snuggle up and feel the feels together, and I try to teach them not to run away from the sad and the hurt. A huge thank you to Pixar for creating Inside Out and Inside Out 2, giving us extra resources to explain emotions to our kids.

In more recent years I’ve repressed less, explored more. When I feel the lid of my suppressed emotions releasing, I don’t fight to keep it on. Knowing that what I am about to experience is normal I feel safe allowing the emotions to wash over me, letting the tears fall and embracing the growth they represent. I know the physical aftermath of a good cry can be eased with a cool washcloth and some ice packs on my eyes. My husband is my anchor, someone I can wrap my arms around and trust to pull me back into the light. My safety net is sleep, because everything looks different in the light of the early morning sun with a fresh cup of coffee in my hands.

What has been the most influential part of my own healing journey is to be credited to a friend Penny, my best friend’s sister. A few years ago, before I had a chance to get to know Penny well, she made an attempt to take her own life. I found myself in a position of supporting my best friend as she processed her emotions at the time while her sister was recovering, physically and emotionally. It was a long journey, and my own experience was preparing me for the worst, but through the frequent updates from my friend I allowed myself to hope. Up until then I never knew anyone personally who survived a suicide attempt. Today their family is like our second family, and I have spent more time with Penny and am thankful for the chance to get to know her – it almost wasn’t. She is a big part of my life, and my kids’ lives, our Aunt Penny. She is the reason I can speak confidently and positively about my journey, and why when that small voice starts to remind me “You could not save your dad” I speak up and tell it “You are right, but I was a child. I didn’t have the tools and resources I have now. Society has changed and will continue to change. Shut up.” …and it does. To Penny, thank you for helping me heal, and helping break the stigma. I love you.

To Penny, thank you for helping me heal, and helping break the stigma.

I love you.

Left to my own devices, needing to tell myself things through the years to heal my 11-year-old girl’s broken heart, I crafted my own message to my inner child. That message contained the type of things that are not the things someone considering suicide or their loved ones should hear. I told myself those things because I didn’t have anything else to say, I didn’t have guidance to heal in a way that would allow me to help others struggling. I knew this and wanting to protect others, I segregated myself from those trying to prevent suicide and set up camp as a survivor. I was too afraid of failure to get involved, but now I know I just needed more time to heal. 28 years later I feel confident speaking up more and sharing my journey with others.

For those of you who struggle with your mental health, I want to tell you what I would say to my dad today: You are loved. You are worthy of love. You are not a failure. You are not, and never could be, a burden. There is no obstacle I wouldn’t stand next to you and face head on. Hell, I’ll drag you through it when you can’t find the strength. You may be considering a choice you think will save us from your pain, but the reality is that choice will pass the pain onto us, and we will carry that the rest of our lives. Given the choice, I choose to live a life with you and with your love, the rest we will figure out together. There are options, and I will fight like hell to find them for you, because you are worth fighting for.

To those who have been shattered by the loss of a loved one ending their own life, I share my message to my 11-year-old self: You are not alone. Child or not, you did not have the right tools. How could you? We do not anticipate needing to be equipped to help someone so wounded. You did not fail him, the adults did not fail him, society failed him. You loved him with all of your heart, and he knows that. His choice was not about what you did or didn’t do, he just didn’t have the resources to heal his emotional wounds. You still want answers to questions, and people have told you to stop looking because you’ll never find the answers. I say, asking questions is a normal part of the healing process, but don’t let it consume you.

Explore the shadows, and explore them often, but don’t live there. Get comfortable with the uncomfortable and equip yourself with the right tools to break free and back into the light. Don’t forget to live your life, it is what our loved ones want for us, those still with us and those gone too soon. Most importantly, don’t let your grief blind you to what you can offer the world. Help others when you can, but also don’t forget to help yourself. There is no end to this journey of healing, but life is never about the destination. This journey will be full of wonderful human connections and glimpses of moments so beautiful you can’t imagine them, so surround yourself with authentic people who love you and enjoy the beauty of life. Only after you have seen such darkness can you fully embrace the beauty of light.

Are you in a crisis? Call or text 988 or text TALK to 741741

Also visit The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention for more resources.

Do you have a story to tell? I often write with my own life experiences, but you are always in my heart. If you have your own story or perspectives to share, I would love to hear from you. Please reach out to me at ChrissieMeasamer@gmail.com. Only together can we break the stigma around mental health and bring more awareness to suicide prevention.